Tunisia is viewed as being ahead of most Arab countries on women’s rights. This is the second part of our cycle of articles written by the brilliant teacher and sister Iman Hajji!

Don’t forget to read the first article about al-Tahir al-Haddad!

Thank Iman!

Today many schools and streets are named after the scholar Tahar Haddad (1899-1935), considered the first feminist of Tunisia. So what happened meanwhile?

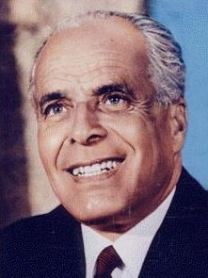

After the gain of independence from France in 1956, Bourguiba passed the Personal  Status Code (Code du Statut Personnel), on August 13th, 1956, as one of the first pioneering pieces of legislation. The PSC enshrined key right to Tunisian women. Leaning on al-Haddad’s visions, the president Bourguiba:

Status Code (Code du Statut Personnel), on August 13th, 1956, as one of the first pioneering pieces of legislation. The PSC enshrined key right to Tunisian women. Leaning on al-Haddad’s visions, the president Bourguiba:

- Institutionalized judicial divorce which could henceforth be demanded by men AND women

- Set a minimum age for marriage

- Abolished the father’s right to wed his minor daughter against her will

- Granted women the right to work, move, open a bank account or start a business without the permission of their husband

- Abolished polygamy which was particularly revolutionary. Polygamy is still legal in the rest of the Arab world.

Scholars did not succeed in mobilizing the public opinion against Bourguiba, as he was prudent and made sure that the grand mufti (highest official of religious law) gave Islamic credence to the legal text in advance, before the promulgation. To this effect he proclaimed: “I worked with Tahar Ben Achour on the code, and it does not contradict the teachings of Islam”. Bourguiba did not want to renounce or to ignore Islam, like Atatürk did in Turkey, but to modernize Islam from the inside. He presented his measures as a modernizing reinterpretation of the Quran through ijtihad (independent reasoning or the thorough exertion of a jurist’s mental faculty in finding a solution to a legal question), rather than an abandonment of religion and therefore called himself “al-mujtahid al-akbar” (a mujtahid is one who exercises independent reasoning (ijtihad) in the interpretation of Islamic law), the great interpreter.

Bourguiba was careful to allow room for religion while working on promoting a modern and reformed application and like Tahar Haddad he recognized, that the first step towards modernization had to be granting women their rights, but also equal respect : “The Tunisian people whether woman or man or child, have to have dignity. Women should have the same dignity and respect and appreciation as men.”

In 1974 Bourguiba explained that he aimed to change the inheritance law, in order to give women the equal right of succession arguing like al-Haddad that the traditional inheritance-law has become obsolete. The reactions in the Arab world were fierce and Bourguiba was at once declared an apostate by scholars like Abd al-Aziz Ibn Baz in Saudi-Arabia and Yusuf al-Qaradhawi in Egypt as for traditional scholars the quranic verse which founds the discriminative law is clear, explicit, and therefore can’t be modified. The respected Tunisian sheikh Muhammad Salah Ennaifer drew a red line reminding Bourguiba that it had already been a major concession for him and other scholars to go along with the code. Conservatives considered the code a violation of Islamic norms and an act of aggression against Arabic culture and Islam. But, like Safwan Masri argues in his latest book “Tunisia, An Arab Anomaly”, “the code was Islamic – in a Tunisian sense. The Code du statut personnel adopted moderate Islamic values that defined Tunisian Islam, and it relied on arguments put forth and defended from within Islam by Tahar Haddad more than two decades ago”. But finally, Bourguiba did not change inheritance in favor of equality.

Bourguiba is nevertheless considered to be Tunisia’s “liberator of women” and the picture  of Bourguiba unveiling women publicly has been memorized until today. By the way : before the gain of independence from France, Bourguiba argued against the unveiling of women as the veil was considered to be a part of Tunisian identity which had to be preserved from the colonist. The women’s question emerged with independence.

of Bourguiba unveiling women publicly has been memorized until today. By the way : before the gain of independence from France, Bourguiba argued against the unveiling of women as the veil was considered to be a part of Tunisian identity which had to be preserved from the colonist. The women’s question emerged with independence.

Bourguiba surely improved the institutionalization of women’s right, but did not explicitly make men and women equal in all respects. He rather created a form of state-feminism that became a strategy to silence opposition while gaining the affections of external allies. Women remained subordinate to men; the husband remained the head of the household.

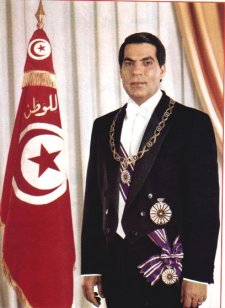

Ben Ali

This strategy evolved during the Ben Ali regime and created a narrow spectrum of activism that allowed women’s organizations to exist, but only within a limited, heavily monitored sphere : the so-called “independent” organizations were supposed to support and not to challenge the government and had to be approved by the Ministry of Culture.  Ben Ali encouraged women’s economic participation by promoting state laws with regards to maternity leave and equal employment, but missed to make efforts to place women in leadership-positions or to protect them from substandard working conditions. Under Ben Ali, women gained the right to transfer their citizenship to their children in the case of marriage to a non-citizen, the right to alimony in the case of divorce, and the right to custody of the children in the case of the husband’s death.

Ben Ali encouraged women’s economic participation by promoting state laws with regards to maternity leave and equal employment, but missed to make efforts to place women in leadership-positions or to protect them from substandard working conditions. Under Ben Ali, women gained the right to transfer their citizenship to their children in the case of marriage to a non-citizen, the right to alimony in the case of divorce, and the right to custody of the children in the case of the husband’s death.

To summerize: legal reforms and a liberal stance supporting women’s rights continued under Ben Ali, but so did the limited freedoms of the feminist movement. Although Ben Ali’s regime allowed for more organizations to operate, feminism was still a state-sponsored and controlled issue.

In 2009, Iman Hajji graduated from the University of Cologne with an excellent Master’s degree in Islamic Studies, Ethnology and Public Law. She held various research assistantships and lectureships at the Oriental Institute of the University of Cologne and at the University of Lyon. In 2009, she published her book “Ein Mann spricht für die Frauen. At-Tāhir al-Haddād und seine Schrift “Die tunesische Frau in Gesetz und Gesellschaft” (Klaus Schwarz Verlag/Berlin), which dealt with the life and work of the Tunisian reformist thinker al-Haddād and his feminist interpretation of Islam. In 2015, Hajji became civil servant and currently she works as a German teacher at a Collège in Meyzieu (Lyon).

Recently, Hajji wrote and submitted her doctoral thesis at the University of Lyon 2 in Arabic linguistics, literature and civilization on “First World War, Pan-Islamism and Tunisian Nationalism. Tunisian figures in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century”. The disputation is to be held in December 2018.